Byte by Byte:Optimizing tokenization for large language models

tl;dr

I was implementing an LLM from scratch using only research papers and was frustrated by the slow performance of my pure Python tokenizer, so I built one in C. bytephase is a high-performance byte-pair tokenizer that uses a hybrid architecture with a Python API and C extensions for core operations.

It uses a trie-based encoding approach to achieve tokenization speeds of 2.41M tokens/sec, significantly outperforming many existing solutions. Training the tokenizer is over 3,000 times faster compared to a reference Python implementation by Andrej Karpathy. The code is available here, and you’re welcome to use bytephase for your own LLM or NLP needs.

Background

Byte-pair encoding (BPE) is a crucial component in modern natural language processing, particularly for training large language models. It was popularized by Sennrich et al. and further adapted to merge at the byte level in the GPT-2 paper: Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. This algorithm is widely used to train some of the most popular LLMs, making it a fundamental building block in AI language understanding.

As part of a project to implement GPT-2 from scratch using only research papers as reference, my first step was to build the tokenizer. I built a pure Python version and it was painfully slow. I understood the algorithm, but if I ever wanted to attempt training my LLM implementation, I needed a more efficient implementation. And this wasn’t a problem that would be solved by throwing compute at it.

I settled on optimizing the tokenizer so it could efficiently handle large datasets quickly without sacrificing flexibility. Enter: The C Programming Language. It was the first language I learned and I’ve always been fond of it, despite the critics, and it would be simple to integrate into the rest of my Python codebase. By the time I was done I truly appreciated all you get for free in Python, and all that has to be implemented in C to provide that functionality.

The Algorithm

The byte-pair encoding algorithm proposed by Sennrich et al. iteratively merges the most frequent pair of characters or character sequences, learning a vocabulary of subword units. This approach allows the model to handle rare words and morphologically rich languages more effectively. The GPT-2 paper adapted this technique to operate directly on bytes rather than Unicode or ASCII characters. This was a clever strategy: by processing raw bytes, the tokenizer can handle any string of text, in any writing system, without the need for pre-processing, effectively creating a universal tokenizer. This byte-level BPE maintains the benefits of subword tokenization while eliminating issues with different character encodings or languages, making it particularly well-suited for training large, multilingual language models.

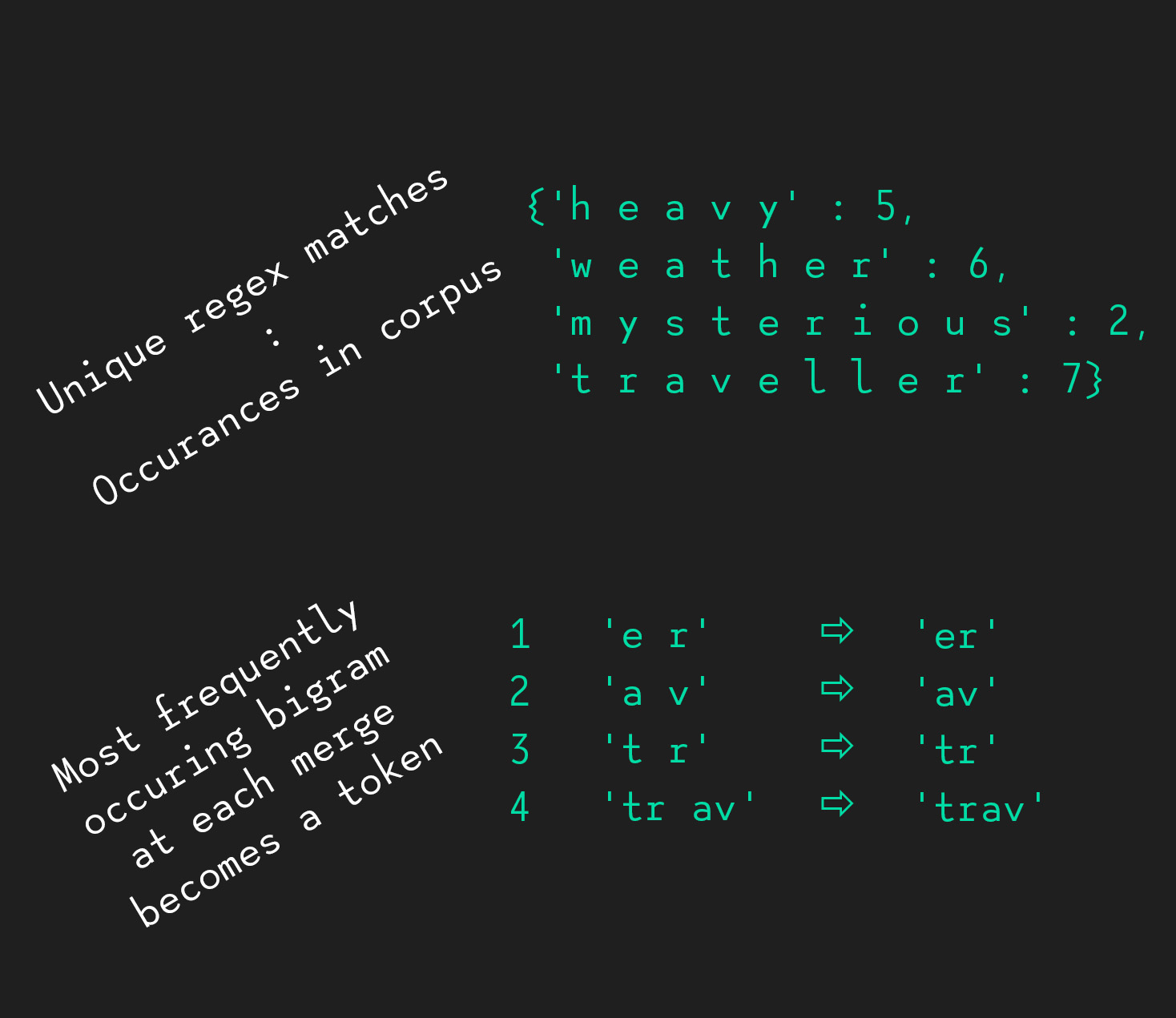

The BPE algorithm begins by splitting words into individual bytes and counting their frequencies. It then iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pair of tokens, creating a new token from this pair, and adds it to the vocabulary. After a token is created, new pair frequencies are calculated and the most frequent pair is merged. This process continues until a desired vocabulary size is reached or no more merges are possible, resulting in a final vocabulary of full words or subword units that efficiently represents the training corpus.

bytephase: a C Implementation

The core of bytephase is built around training the tokenizer to a target vocabulary and then encoding text into token IDs for use in LLM training and inference, both of which are implemented as C extensions of Python. Aside from the speed gains from using C, I also worked to optimize elements of the algorithm to avoid what I saw as unnecessary and expensive work.

Many existing BPE implementations recalculate byte-pair statistics for the entire training corpus after each merge step. This is highly inefficient and I instead update statistics on the fly as adjacent bytes are merged into a single token. Once we find a pair to be merged, there are a maximum of four operations required:

Update left context (if exists):

- Decrement the frequency of the bigram formed by the left token and the first token of the pair.

- Increment the frequency of the bigram formed by the left token and the new merged token.

Update right context (if exists):

- Decrement the frequency of the bigram formed by the second token of the pair and the right token.

- Increment the frequency of the bigram formed by the new merged token and the right token.

if (*unigram_1 == (*max_node)->bigram[0] && *unigram_2 == (*max_node)->bigram[1])

{

if (unigram_L != unigram_1)

{

unigram_L = unigram_1 - 1;

update_bigram_table(*unigram_L,*unigram_1, -1 * text_chunk_node ->count, bigram_table);

update_bigram_table(*unigram_L, token_idx, text_chunk_node ->count, bigram_table);

}

unigram_R = unigram_2 + 1;

if (*unigram_R != 0)

{

update_bigram_table(*unigram_2,*unigram_R, -1 * text_chunk_node ->count, bigram_table);

update_bigram_table(token_idx, *unigram_R, text_chunk_node ->count, bigram_table);

}

*unigram_1 = token_idx;

// ... (memory management code omitted for brevity)

}

Finally we replace the first token of the matched pair with the new merged token ID and shift the rest of the byte sequence one place to account for two tokens becoming one. At the end of training, tokens are returned as byte sequences which are reconstituted from the tokens using a depth-first search algorithm.

The other major optimization implemented in C is a pair of methods for encoding text into a token sequence. A trie data structure for efficient storage and rapid lookup of tokens, which is crucial for high-speed encoding. The trie is constructed during the training phase or when a training file is loaded, while decoding operations are handled by a dictionary.

This trie structure allows for O(n) time complexity for both insertion and search operations, where n is the length of the token. This is a significant improvement over naive string matching approaches, especially for large vocabularies.

Python Integration

While building this for myself was extremely rewarding, I ultimately wanted it to be useful and not just an intellectual exercise. To maintain ease of use while leveraging C’s performance benefits, I designed a Python API that interfaces with the C extensions. This hybrid approach allows users to interact with the tokenizer using familiar Python syntax while the computationally intensive tasks are handled by C extensions.

The Python Tokenizer class acts as a wrapper around the C functions, handling the initialization, training, encoding, and decoding processes. This high-level interface abstracts away the low-level details, providing a seamless user experience. I also leveraged the highly optimized regex library (also written in C!) since I found my attempts to implement Perl-style regular expressions in C were slower.

Training the tokenizer can be done in as little as two lines of Python:

tokenizer = Tokenizer()

tokenizer.train("path/to/your_data.txt", vocab_size=128000)

The train method handles reading the file in chunks, regex parsing and calls to C extensions. By default, the Tokenizer class uses a 2MB buffer size, but you can specify a different buffer size when instantiating the object.

def train(self, file_path: str, vocab_size: int) -> None:

text_stats = Counter()

for matches in self._process_chunks(file_path):

text_stats.update(matches)

text_stats = dict(text_stats)

num_merges = vocab_size - 257

# This call to `train` is implemented in C

merges = train(text_stats, len(text_stats), num_merges)

self.decode_dict = {idx: bytes([idx]) for idx in range(256)}

self.decode_dict[self.eos_token_idx] = self.eos_token.encode("utf-8")

for idx, merge in enumerate(merges, start=257):

byte_array = bytes(merge)

self.decode_dict[idx] = byte_array

self._trie = build_trie(self.decode_dict)

Comparing bytephase to other implementations shows significant gains. Despite having 3,000 times more merges, bytephase trains faster than a reference pure Python implementation by the AI educator Andrej Karpathy. It also uses less than half the memory since Karpathy’s implementation requires reading all text into memory. It’s not a perfect comparison, but does demonstrate the efficiency gains achieved through the C extensions.

| Tokenizer | Merges | Training Time (s) | Memory Usage (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| minbpe (Karpathy) | 10 | 212.31 | 755.58 |

| bytephase (Arnav) | 30,000 | 193.86 | 361.48 |

These numbers were achieved by testing on the first 10,000 elements of The Pile dataset. I’m working on adding more benchmarks and will update this post when those are ready.

Performance Optimization

One of the key challenges in developing bytephase was balancing memory usage and speed. To address this, I implemented two distinct encoding modes in the encode method:

- Training mode: Optimized for lower memory usage, ideal for processing large datasets and conserving memory during training.

- Inference mode: Maximizes speed at the cost of higher memory consumption, better for real-time applications.

def encode(self, input_text: str, train_mode: bool = True) -> List[int]:

if train_mode:

chunk_iterator = self.compiled_pattern.finditer(input_text)

return encode_train(chunk_iterator, self._trie)

else:

text_chunks = self.compiled_pattern.findall(input_text)

return encode_inference(text_chunks, self._trie)

Both encode functions called here are implemented in C and use the trie built during training to transform text into a list of token IDs (integers). The only difference is encode_train accepts an generator object and encode_inference reads all the text chunks from the regex parsing into memory. All of this is abstracted away in the Python API and the user can switch between the two with a simple boolean flag.

These optimizations resulted in impressive performance metrics:

| Mode | Speed (tokens/s) | Memory Usage (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 1.42M | 735 |

| Inference | 2.41M | 19,220 |

These tests also used the first 10,000 elements of The Pile.

Lessons Learned and Future Improvements

Developing bytephase was a fascinating and rewarding deep dive into the intricacies of tokenization and its impact on LLM performance. Some key takeaways include:

- The importance of efficient data structures in NLP pipelines

- The trade-offs between memory usage and processing speed

- The value of low-level optimizations in high-performance ML systems

Future improvements could include:

- Implementing parallel processing for even faster tokenization, and explore adding GPU support

- Exploring more memory-efficient trie implementations for larger vocabularies

- Adding support for custom tokenization rules to enhance flexibility

Conclusion

By implementing this critical component from scratch, I’ve gained invaluable insights into the low-level operations that power modern AI systems and important experience balancing theoretical understanding with practical implementation. While BPE is currently the most popular method of tokenization, this will likely not last forever.

As AI systems continue to grow in size and complexity, the ability to optimize and fine-tune every component of the pipeline becomes increasingly crucial. Projects like this showcase the kind of deep, system-level understanding that’s essential for pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in AI.

For those interested in exploring the code or contributing to the project, bytephase is open-source and available on GitHub. I welcome feedback, contributions, and discussions on how we can continue to improve and optimize the fundamental building blocks of AI systems.