Do Image Classifiers Deepdream of Electric Sheep?

tl;dr

This investigation serves to inform how deep learning models interpret styles, themes and elements, and how we can begin to interpret and control the outputs by diving into the internal workings. It also raises the question: if we can understand how AI classifies an image, can we alter it—maliciously or not—to be blind to a specific object or style? And why would we want to?

I built a simple deepdream algorithm to visualize what aspects of an image a machine learning model uses to make classification predictions. I then pinpointed the parts of the model that were responsible for correctly predicting a variety of objects in order to modify the internal parameters to effectively “blind” it. After a quick lobotomy it made wildly inaccurate predictions when fed the same images.

Background

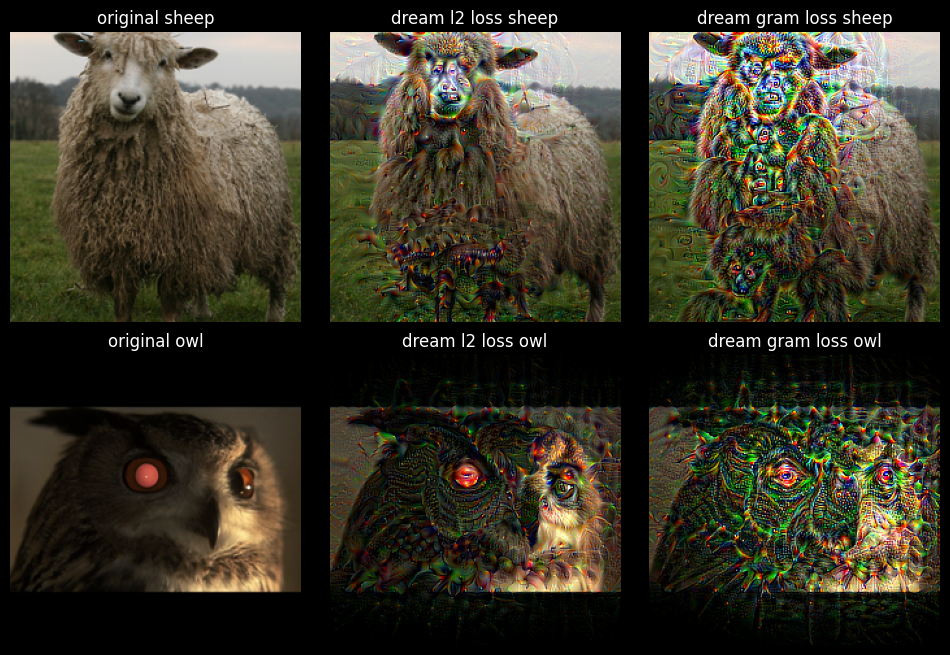

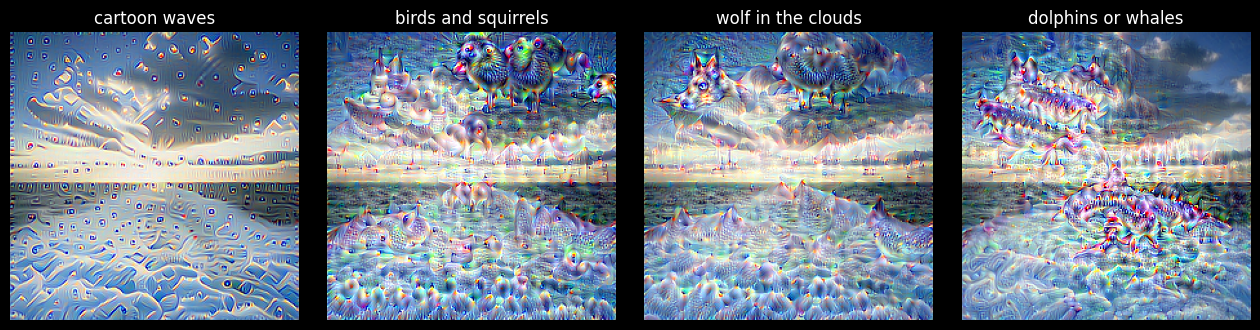

The deepdream algorithm takes a machine learning model that was trained on an image dataset and feeds it new images, but instead of trying to predict what it sees, the model generates a new image revealing strange and psychedelic patterns. It was originally developed at Google and often tries to understand elements of this new image based on the set it was trained on, generating eyes, animal faces and swirling shapes. It can even find animals hiding in clouds.

When training most machine learning models, a loss is calculated at each step that captures the difference between the model’s predictions and actual target values. The model’s goal is to minimize this loss by updating its parameters accordingly, and it knows how to do this update by using gradient descent.

When the updating step is changed to go in the opposite direction, or gradient ascent, it uses this value to update the input image, generating the dream image and revealing latent patterns. The resulting images are highly dependent on the model architecture and the dataset it was trained on. This technique can also be used in mechanistic interpretability to visualize what aspects of an image the model is using to make its predictions in each layer.

I wanted to see how the deepdream algorithm responded to a few concepts. What does it see when it looks at clouds? Can it tell the difference between a human eye and one belonging to an animal? How similar is a container ship and cruise ship to the model? How does it determine which of these two massive ships is which? What is it looking for; what is it looking at?

I used a VGG19 image classifier pretrained on the ImageNet-1k dataset. First, we hook into the model to record the outputs of each layer. Then we pass an image into the dream function and can see what effect each layer is responsible for. In an initial test using a photograph of clouds over the ocean taken by Allan Sekula, the model saw elements of animals it was trained on appearing in the cumulus.

def gram_matrix(img):

features = einops.rearrange(img, "b ch h w -> b ch (h w)")

gram = torch.matmul(features, einops.rearrange(features, "b ch hw -> b hw ch"))

return gram.sum()

def dream(

input_image,

model=hooked,

layer_outputs=layer_outputs,

layer=33,

channel=None,

learning_rate=0.01,

epochs=30,

loss_fn=None,

loss_weight=1e-5,

):

input_image = copy.deepcopy(input_image.detach())

dream = input_image.to(device).requires_grad_()

model = model.to(device)

for _ in range(epochs):

model(dream)

if loss_fn is None:

if channel is None:

loss = layer_outputs[layer].norm()

else:

loss = layer_outputs[layer][:, channel, :, :].norm()

else:

if channel is None:

loss = loss_weight * loss_fn(layer_outputs[layer])

else:

loss = loss_weight * loss_fn(layer_outputs[layer][:, channel, :, :])

dream.grad = None

loss.backward()

dream.data += learning_rate * dream.grad

dream.data = torch.clamp(dream.data, 0, 1)

return dream

I experimented with two loss functions, l2 norm and a Gram matrix. Using the Gram matrix in calculating the loss is typically used in style transfer applications, like taking a photograph of a dog and generating a new image of it in the style of a Picasso painting. In this context using this loss is designed to make the dreams follow the style of the input image. Also, since the focus of the dream function is to modify the input image, we need to zero the gradients of the image tensor directly so they don’t accumulate between epochs, unlike a typical training loop.

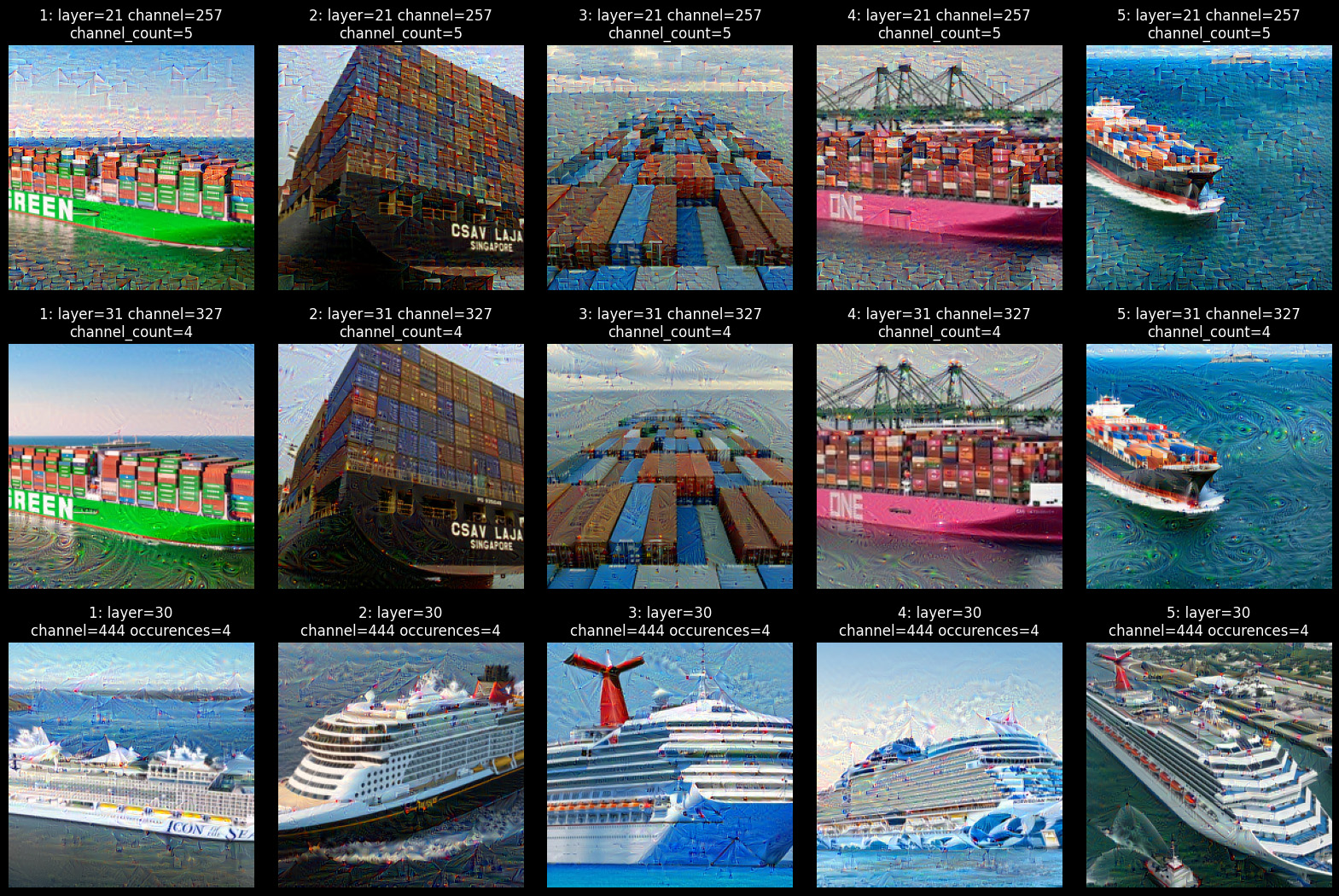

Mechanistic interpretability: What makes a ship a ship?

I chose to focus on images of ships because they contain a lot of diverse elements. There are the natural aspects of the sea and clouds as well as distinctly engineered elements: the sharp lines of the hull, the repeated patterns of windows or containers and rows of antennae and smoke stacks.

After recording the activations as these images move through the model, we can begin to see what parts of the model are responsible for correct predictions, and at those points what aspects of an image are most important. When the model is given a container ship, the repetitive boxy patterns manifest in earlier layers. Later on we see other layers picking up on the water around the ships. This makes intuitive sense and it’s interesting to see how similar a collection of floating point numbers can learn to focus on the same things a human would. Similarly with cruise ships, the model seems to again focus on water, but also relies on the silhouette of the vessel, particularly the peaks formed by antennae.

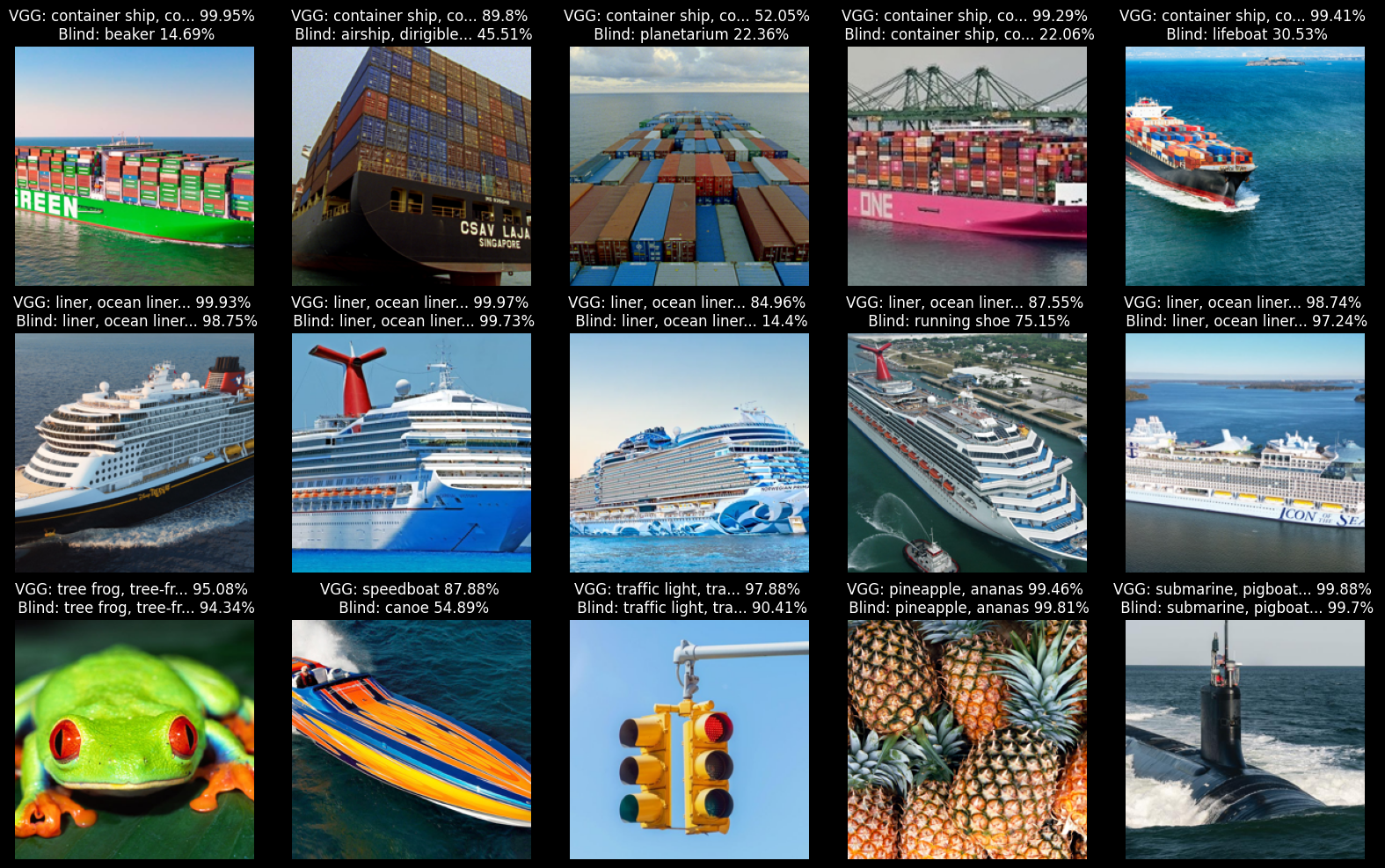

But what if the image classifier no longer knew how to recognize a container or cruise ship? If we focus on the activations that were most associated with a container vessel—by analyzing the outputs recorded from the hooked model—and zero them out or inject random noise, we can blind the model so it makes incorrect predictions. We pass the same activations that were used to visualize the crucial elements above to blind_model and see how it performs before and after.

Channel = namedtuple("Channel", ["layer", "channel"])

def blind_model(model, channel_counts, start_layer=20, top=4, blind_method=zero_channel):

model = copy.deepcopy(model).to(device)

for layer, layer_count in channel_counts.items():

if layer < start_layer:

continue

channels_to_blind = [Channel(layer, channel) for channel, freq in layer_count.most_common(top)]

for c in channels_to_blind:

blind_method(model.features[c.layer], c.channel)

return model

After blinding it can no longer correctly predict container ships. It manages in once case but the confidence drops markedly and to a level that would typically be ignored. The model can largely still identify “ocean liners” except in one case, showing that there are not enough shared activations between the two classes so that blinding the model to one class cripples it for the other. The model also still mostly classifies the control images correctly. Interestingly, while it fails to classify the speedboat image, it still knows it’s some type of water vessel.

Implications

Understanding how an image classifier makes specific predictions can be extremely powerful. It can allow malicious actors to try to modify models to blind it to specific elements or to create images that specifically mimic certain features in order to deceive the model. As AI is deployed to automate more tasks, understanding its failure points is critical for developing safe and effective systems. It also informs our understanding of how these models work internally, how and what they are learning and what parts of the model are responsible for which tasks.

Even though VGG19 is no longer a cutting-edge AI architecture, it’s still widely used in transfer learning where its weights serve as the basis when developing new models. Depending on available resources it may be an appropriate choice for some computer vision tasks. Developing a deeper understanding of how these models work is crucial, as is finding ways to visualize these elements to communicate these concepts to a wide audience.

The complete code for this project can be found here.